The 1981 murder trial of Alwyn Peter made Australian legal history when his defence lawyer successfully argued that charges of murder and manslaughter were inappropriate for dispossessed, semi-tribal Aborigines.

The 1981 murder trial of Alwyn Peter made Australian legal history when his defence lawyer successfully argued that charges of murder and manslaughter were inappropriate for dispossessed, semi-tribal Aborigines.

In December 1979 at the Weipa Aboriginal Reserve on Queensland’s Cape York Peninsula, Alwyn Peter killed his girlfriend Deidre Gilbert. She was 19. He was 22. He stabbed her to death in a drunken rage.

Should this one incident have moved us? Wasn’t it, after all, “just another black death”…an unfortunate domestic killing triggered by alcohol and anger, so commonplace in the Aboriginal community that it might hardly raise an alarm?

It was indeed, just another death. But this one, for whatever quirk of historical circumstance, did raise the alarm and raised it loud. For a short, significant time, Deidre’s death focused attention on a much bigger tragedy that had been gathering momentum unheeded for years – not the fate of one Aborigine, but the slow, systematic annihilation of a people by its own hand.

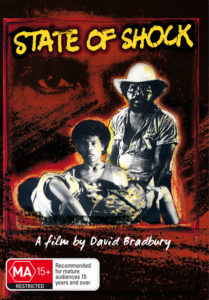

Aboriginal Australia was, and still is, killing itself…and no one seems to care. Award winning filmmaker David Bradbury took up Alwyn and Deidre’s story to find the cause of this genocidal trend.

State of Shock is his attempt to look at Black Australia without prejudice to white or black. The picture which emerges is neither pretty or romantic nor has it been shown before.

Bradbury and his team use scenes from the stage play State of Shock starring Ernie Dingo and Lynette Narkle juxtaposed with Alwyn’s life. The film takes an intimate look at. Alwyn and his family, showing how their broken culture and the destruction of traditions has left Aboriginal people lost and powerless, turning their anger inwards on themselves.

It was not always like this. Mapoon was the site of the first north Queensland mission, founded in 1891. Here Alwyn’s elders as children were taken from their mothers and brought up “the Christian way.” Tribal language was forbidden. Tribal law and custom was deemed satanic…and a lifestyle of 40,000 years was discarded. But in spite of all this, Mapoon still proved to be a paradise. It offered land for hunting and fishing and some restoration of tribal heritage, so vital to the Aboriginal identity.

Paradise was lost in 1957, the year the Queensland Government passed the Comalco Bill…the year Alwyn Peter was born. The Mapoon people were stripped of their last pretence of any control over their lives and land which was handed to the mining companies.

In 1963 the church abandoned the Aborigines to make way for proposed mining. Most left the mission but a small band stayed…only to see their homes burnt to the ground under orders of the Department of Native Affairs. The Mapoon people were sent to settlements throughout north Queensland, among them the desolate mining town of Weipa run by Comalco.

The Aborigines, including Alwyn’s family, depended on the mining company for whatever work was handed out to them, for their houses, for their existence. But there was no fishing or hunting to be done here. Different tribes were forced to live together on a small reserve.

Life degenerated into alcoholic despair; self-mutilation, suicide and attacks on loved ones has created a murder rate at Weipa higher than that of New York City or Chicago.