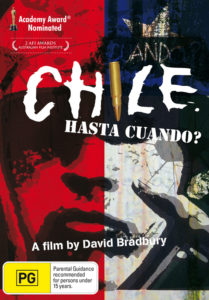

A portrait of a brutal military dictatorship made during a three month visit to Chile in 1985 by David Bradbury.

A portrait of a brutal military dictatorship made during a three month visit to Chile in 1985 by David Bradbury.

This powerful documentary traces the 12 years from 1973 to 1985 of General Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship and whose forces seized power in a bloody, US-backed coup.

Marxist president Salvador Allende was left for dead and with him any hopes of democracy remaining in Chile. Military intimidation of the population, indiscriminate arrests, murder, torture and disappearances were facts of Chilean life.

The footage reveals a country torn with civil strife and political unrest.

The Sydney Morning Herald Film Review

Chile: Hasta Cuando? (When Will It End?) reveals the tragedy of a divided country, a country on the verge of eruption.

David Bradbury keeps searching for the perfect socialist democracy, and his failure to find it often results in illuminating, angry and sometimes polemical documentaries.

His last two films have been like that. In Nicaragua No Pasaran, a portrait of post-Somoza Nicaragua, his tenacious style of film journalism was turned against the US Administration of Ronald Reagan, and to a lesser extent, the failure of the Sandinistas to embrace democracy.

Whether you feel the balance was right probably depends on who you voted for at the last election. Chile-Hasta Cuando? is a less ambivalent, even angrier film. Here there is no redeeming side to the military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet, no paradise lost. Chile is a film full of the pain of an abused people – a people in rebellion against institutionalised torture and murder.

Once again the US is the puppeteer, this time Pinochet is its puppet, and the people are the victims. Bradbury shows very clearly and eloquently who these victims are. There are some moments of excruciating rage and tragedy in Chile – Hasta Cuando?, particularly the final scenes outside a morgue when two women learn that the bodies of their kidnapped husbands have been identified. “How long will this go on,” cries a woman swaying with grief.

This sort of scene is what distinguishes Bradbury’s documentaries. In most respects he constructs conventional Four Corners-style programs – a mixture of voice-over narration, talking heads and news cameraman’s footage – but sometimes the footage is extraordinary. He has the knack, like the subject of his first documentary, the late Neil Davis, of being there when things are happening. (In fact, Bradbury seems to share that craving for excitement and danger that war cameramen have. The difference is that while they usually record and dispose of their film on the nightly news, Bradhury couples it with his political sensibilities – he judges what he sees, and puts it all together.)

In these scenes, the hand of the film maker retreats and the audience feels a more direct connection with the subject. His films work best when he allows the audience this involvement – a subject which may seem remote becomes accessible. In No Pasaran, scenes in the market, with a group of women arguing over food shortages, say more about the internal and external politics of the country than all the polished rhetoric of Thomas Borge, the founder of the revolutionary movement.

In Chile – Hasta Cuando? Bradbury’s footage of demonstrations on the streets of Santiago have the same effect. We see the terrible randomness of the repression, as soldiers in riot gear calmly walk up to those on the edges and drag them off to the trucks.

Similarly, we see the great courage of ordinary people – the middle-aged women who turn their backs on the water-cannon while refusing to disperse. Bradbury’s cheekiness also results in some illuminating footage of the collaboralion of the middle and upper classes, which keeps Pinochet in power. One wealthy family invited Bradbury and his crew to dinner, and were frank in answering his questions. The husband, an industrialist, says dead-pan: “This is a government that lets you do what you like – under certain rules. The only freedom we don’t have is political .” His bejewelled wife scoffs at the idea that people are being tortured: “Why torture someone when you can shoot them ?”

The similarities to the brilliant Argentiman film The Official Story, now playing in Sydney, are chilling. A small criticism of Chile is that Bradbury’s narration is inadequate. His voice lacks training, and sometimes the content becomes preachy, which is always the danger with such a politically committed film-maker.

The Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday, May 22, 1986