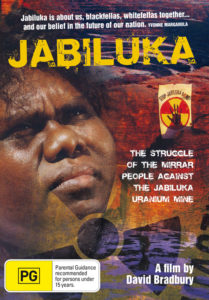

The struggle of the Mirrar people against the Jabiluka Uranium mine.

The struggle of the Mirrar people against the Jabiluka Uranium mine.

“Jabiluka is about us, blackfellas, whitefellas together…and our belief in the future of our nation.”

In 1997, Energy Resources of Australia (ERA) pushed to open a new uranium mine surrounded by the World Heritage listed Kakadu National Park.

The traditional Aboriginal owners told the company and the government that they did not want this mine. They were concerned about its effects on their country and culture. Environment groups and many others also worked to stop Jabiluka and other new uranium mines.

Many Australians asked how could we threaten the cultural and environmental values of our most famous world heritage listed national park – Kakadu. How could we put at risk the culture and the lives of the indigenous people of Kakadu with a new uranium mine at Jabiluka?

The Federal Government of Australia, the government of the Northern Territory, mining company Energy Resources of Australia (ERA) and the Northern Land Council all wanted uranium mining to go ahead at Jabiluka but the Mirrar people say ‘No’.

Since the Ranger mine at Jabiru was given approval in 1978 Mirrar opposition to the proposed Jabiluka mine strengthened…19 years on. Living and social conditions amongst Kakadu’s indigenous population had worsened and the people were deeply concerned about the impact of mining on their lives and the unknown consequences of storing crushed and pulverised radioactive wastes on their land.

In the culture of the Mirrar, Jabiluka is so sacred not even traditional owner Yvonne Margarula could speak about it. And yet knowing this the then Federal Environment Minister Robert Hill gave the green light to the Jabiluka mine despite the negative findings of a social impact study and warnings from his own departmental bureaucrats that the mining company’s environmental impact statement was deficient in key areas.

Jabiluka was the first of 26 proposed new uranium mines the Howard Government had before it for approval. In this important film twice Academy Award nominated director David Bradbury captures the controversy over Jabiluka.

The Jabiluka mine was proposed to be underground, below the flood plain in an area infamous for its big wet season and beside Kakadu’s famous wetland. ERA planned to clear a mine site and bulldoze a road 22.5 kilometres long to truck the ore to the Ranger mine where it would be processed into yellowcake and then exported.

ERA’s Philip Shirvington (CEO saw management of the mine as a simple matter of a job they do well: ‘We don’t add any radioactivity to what’s already there naturally,’ he said. But ‘not so’ said the traditional owners, scientists and environmentalists who were concerned that the tailings would remain radioactive for the next 250,000 years.

The film Jabiluka clearly shows how the Mirrar were given no choice over the Ranger mine, how they were caught in a misleading process to consent to a lease over Jabiluka and how they resisted those same pressures to allow mining to proceed.

The story of Jabiluka is also significant because it raises questions about the real value of ‘Land Rights’. The Mirrar people now own their land but are wondering whether that actually means anything. On December 16 as part of her steadfast campaign Yvonne Margarula took her case to the Federal Court of Australia to prevent the Federal Government granting ERA approval to export uranium from Jabiluka.

She continued the fight first taken up by her father Toby Gangale… for the right of her people to live in harmony with 40,000 years of cultural tradition. “We know we own the country” she says. “We know. We born the country, and we live the country. It is our country… black country… not white country.”

In 1978 Professor Manning Clark visited the ‘Top End’ and was left with an enduring impression of its abundant cultural treasures, of its pristine wetlands and majestic escarpments. Following that visit he stated clearly his opposition to mining Kakadu.

“It would be an evil day in the history of this country if the white man once again showed the black man that nothing else mattered except material grandeur.

Is it too much to hope that the natural paradise of Kakadu National Park might be a setting not so much for a human paradise but at least a place where the white man and the black man can at last live in harmony with each other?”