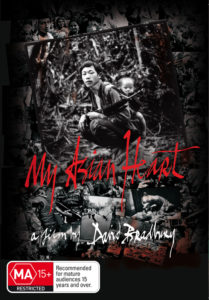

Filmmaker David Bradbury follows Australian photojournalist Philip Blenkinsop, who goes to extremes to expose human rights abuses and forgotten wars in south-east Asia.

Filmmaker David Bradbury follows Australian photojournalist Philip Blenkinsop, who goes to extremes to expose human rights abuses and forgotten wars in south-east Asia.

During the heyday of classical magazine photojournalism in the l970s, Cornell Capa of Magnum Photo agency coined the phrase concerned photographer to mean “a photographer who is passionately dedicated to doing work that will contribute to the understanding or well being of humanity.”

Despite today’s cynical and fast world turnaround of images and headlines where traditional photojournalism has become swamped by a torrent of lifestyle reporting and celebrity paparazzi photography, there are some who still care.

Classic photojournalism is still alive, though struggling, amongst a new generation of photographers. Philip Blenkinsop (44) is one of them.

In l989 Blenkinsop quit his job on The Australian newspaper, sold his Austen Healey Sprite sports car, bought two Leica cameras…and a one way ticket for Bangkok. He was escaping suburbia for the heartbeat and chaos of Asia. He began documenting conflict, war, life and death in all its forms throughout Asia. Lesser known wars.

Philip trekked into the forbidden zone of Laos to photograph the persecuted Hmong minority, suffering constant helicopter rocket attacks from the vengeful communist government. Thirty years after the Vietnam War, they have not forgiven the Hmong for siding with the Americans and the CIA. Since then Philip has been on a race against time to alert the world to their situation. He financed his personal crusade to Washington to use his photographs to help get word out on the Hmong amongst Congressmen when his award winning spread in the London Times failed to help them out. He got a sympathetic response that resulted in nothing.

“I think you do have a responsibility when you are one of the few people there. Other journalists give me a hard time and say, ‘ Forget about it Philip. It’s just a story. Get on with it. I find that attitude very hard to stomach,” he says. Philip went in search of the mysterious Maoist guerillas in Nepal and found them. In l998 he smuggled himself into the jungles of East Timor and went with the Falantil guerillas for three weeks photographing their forgotten war against the Indonesians before independence.

But Philip is not just another war photographer seeking a quick adrenalin fix. He regards himself as an artist and is equally at home photographing the bizarre as he is documenting conflict and human suffering. Photographing a slaughter house for dogs in Thailand or Saigonese youth racing themselves at adrenalin fed speed on motorbikes without helmets through traffic crowded streets finds Philip in his element.

He doesn’t do it simply for the thrill but as he puts it himself, “to counteract the prettified picture reporting that is presented to us everyday. My task is simple: to show that which you cannot see somewhere else.”

For that reason the daily press often reject his work, so he has been forced with growing critical success to exhibit in galleries and museums around the world.

While much more at home working far away from prestigious locations where his work hangs in Paris, New York or Sydney, he has rattled the photographic world with his eye. Practically unknown in Australia, Philip has won many international photographic prizes for his work including Amnesty International’s award for Best Photographer of the Year in 2003. This award for his haunting portraits of the Hmong tribes people hiding out in the Forbidden Zone of Laos where Philip smuggled himself in to take these photos. The Hmong sided with the US military to rescue downed pilots during the Vietnam war. When the US lost that war, they abandoned the Hmong leaving to the mercy of a revengeful, communist Laotian government.

He lives with his French raised wife Agnes (also a photographer) in Bangkok and…his pet snake. The film will follow him on assignment to China, Nepal during the pro democracy uprisings, to Cambodia. The film will also document what drives Philip and others of his ilk to risk life and limb struggling to have their work supported and most importantly to have an impact, only to receive little if any response.

Despite what some would regard as a critical voice in today’s society, “concerned photographers” pay a huge price for their art and the message they are desperate to communicate. Is it that society has lost interest, dazzled and distracted by celebrity and tabloid infotainment? Do we no longer value the stories that people like Philip at great danger to themselves bring to us? Or is there a concerted effort to suppress the work of these modern day crusaders?

The film will explore Philip’s mostly ‘hate’ rather than love relationship to today’s electronic media and how he combats the emphasis by picture editors in far away cities to sanitise our response to Asia, to marginalize and ignore altogether those struggles that they deem not to have significant newsworthy value, even though hundreds of thousands, millions of lives may be at stake.

Philip is in that tradition of a few legendary Australians like Neil Davis, like Wilfred Burchett who have abandoned Australia for a life in Asia so they can tell it like it is.